Earth is rapidly transforming in the face of climate change. While this is a global phenomenon, the effects of climate change are not felt uniformly. Some regions experience pervasive drought, while others face aggressive rains. Both scenarios contribute to a reorganization of basic environmental planning to best utilize the resources available. Using geophysical instrumentation and techniques can allow researchers to understand how natural resources may be affected by changing climate, and how we can manage these changes properly.

The NSF GAGE and SAGE Facilities operated by EarthScope Consortium support fundamental scientific efforts at the intersection of solid Earth geophysics and climate. At this year’s NSF SAGE/GAGE Community Science Workshop, researchers spoke about geophysical techniques applied to issues that not only interest geophysicists, but can also be used to understand the full extent of environmental hazards and how to monitor them.

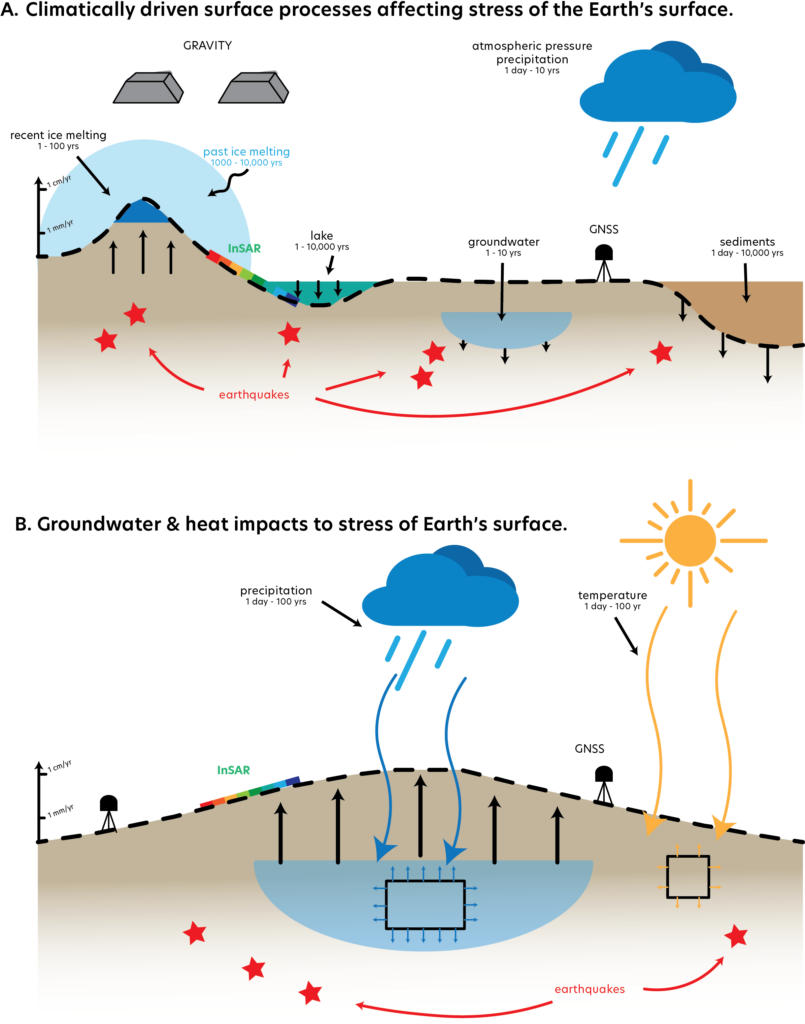

Dr. Roland Bürgmann spoke about the subtle influence of climate and weather on surface deformation and earthquakes. In 2024, most of the general public is familiar with the perils of climate change—global warming, sea level rise, increased rain in some areas and increased drought in others. Processes associated with climate and weather, such as temperature and precipitation, can impact surface features by heating the surface, redistributing water storage in the subsurface, and increasing or decreasing sedimentation rate, all of which can affect stresses around faults.

And when temperatures rise, ice sheets melt. This causes the surface below the ice sheets to rebound upward because it no longer accommodates the weight of the ice on top of it. This ultimately redistributes surface stress, causing deformation. In a warmer world, rainy regions see even more rain. Some fault surfaces can be made more slippery with increased fluid pressure, which can be influenced by seasonal cycles or long-term changes in groundwater and precipitation.

Drought leads to complicated groundwater detection

Conversely, drier areas will experience longer and more extreme droughts in a warmer world. Areas that have historically relied on surface water supplies, such as agricultural areas in California, are shifting their water resource usage to rely more on groundwater. This poses a great challenge to communities dependent on smart utilization of groundwater resources because climate change has stressed the surface supplies and even groundwater reserves. However, groundwater is difficult to monitor and measure, chiefly because it is underground. The systems that are monitored are done so sparsely. So, finding clever ways to estimate groundwater change is key for managing it sustainably. This is where the tools of geophysics can be utilized to help communities transition to more resilient resource management.

GNSS and InSAR are a couple of the techniques most commonly used to collect data to measure surface deformation, like uplift or subsidence, measured both on the ground and via spaceborne satellites. But how might surface deformation be related to groundwater storage?

Unlike most visualizations depicting groundwater as a layer of water in the subsurface, the subsurface can instead be thought of as a sponge that soaks up water, storing it in the water-filled spaces between grains of sediment. When there is a lot of water in the sediments, the ground can swell, but when that water is removed, the sediments collapse together. Changes in groundwater directly impact surface elevation in that case, so we can use surface deformation as a proxy for groundwater supply. Characterizing where and when groundwater might be well-off or depleted is therefore extremely important for communities to make informed decisions about their water resources.

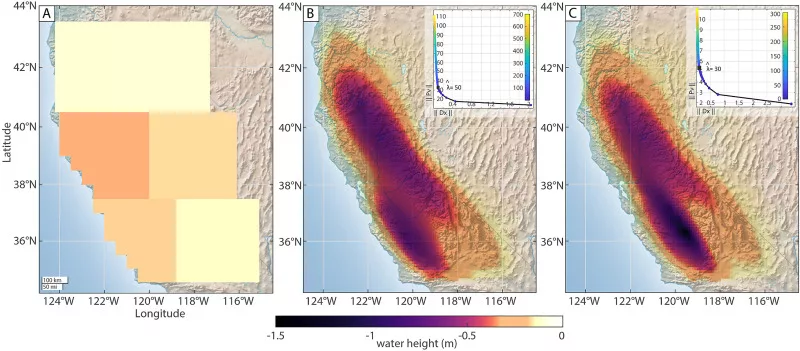

Dr. Grace Carlson combines the use of GNSS and measurements from gravity satellites (GRACE and GRACE-FO) to understand changes to Earth’s surface as a result of varying surface and groundwater storage in California’s Central Valley. Previously, this joint approach with GNSS and GRACE has been used to study changes in surface water storage across California. GNSS is great for understanding small-scale local changes, while GRACE can help at the regional scale.

Work done by Carlson and her team investigates how the extreme drought of 2020-2021 impacted groundwater and surface water storage. In addition to the drought, farmers began turning to groundwater pumping to supplement low surface water reserves, which exacerbated aquifer loss. This resulted in increased subsidence of the valley floor. Carlson and team marry together the different data types in a method called inversion, which estimates the values of a particular variable of interest using a set of observed data. These observations come from GNSS, InSAR, and GRACE-FO.

Modeling groundwater flow with remote sensing observations

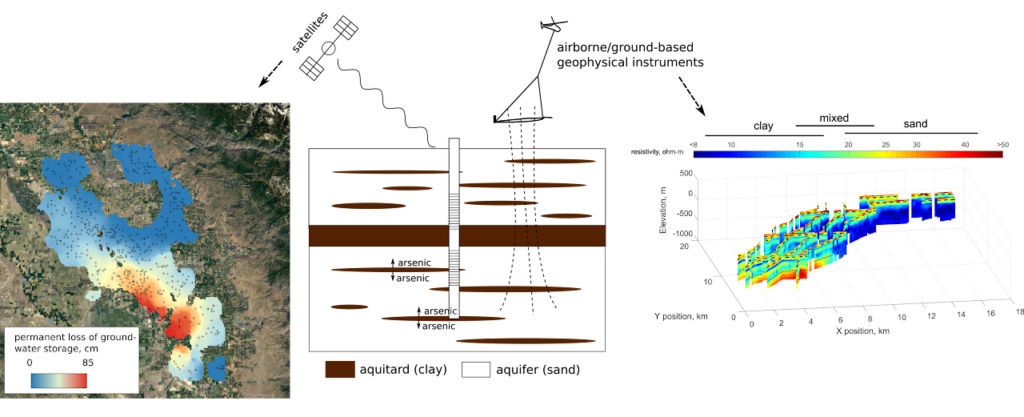

Dr. Ryan Smith also uses geophysical methods to study groundwater, putting them to work with models and machine learning. Smith integrates InSAR data, airborne geophysical data, and ground-based geophysical measurements to improve upon groundwater models. Like in Carlson’s work, these tools can help fill in knowledge gaps about groundwater resources and surface deformation. Smith links rock and sediment types to surface deformation in his work, mapping where the land is more sensitive to groundwater change in the Central Valley.

He focuses specifically on clay, which compacts when water is removed. This connection is extremely important because it allows scientists to figure out whether differences in surface deformation are related to differences in groundwater depletion or just due to variations in sediment type. This helps us understand where groundwater is and where it flows, which will help local authorities better understand the limits of their resources as they are continually impacted by changing climate.

Creative combinations of ground-based and satellite instruments, conventionally used to study things like earthquakes, are helping us to better understand the more complex and sensitive systems of groundwater. The work done by Carlson’s and Smith’s teams is essential front-line work that will serve to help local natural resource authorities better plan for changing climate norms. Continuing to apply these geophysical tools and methods will enable scientists and communities to better understand how natural resources are affected by climate change.