In geodesy, change is usually the most interesting thing to measure — dynamic events where data can tell a revealing story. Unfortunately, dynamic environments can also threaten the instruments, knocking them out juuuust as that story was getting good. Working out how to keep the data flowing is a process of trial and error, finding the weak points and experimenting with ways to harden them, although no design is invulnerable.

The engineers that keep the Caribbean portion of the Network of the Americas (NOTA) running know this well. These GPS/GNSS stations have important roles to play tracking tectonic motion in the region, but some are extremely remote and logistically complicated to reach for maintenance. That has made repairs for hurricane damage a constant challenge.

Last year, EarthScope engineer Adam Woolace deployed a new station package designed to stand up to hurricanes at two Caribbean stations — including one in Jamaica that was immediately tested by Hurricane Melissa.

Heavy metal

Many Caribbean NOTA stations are located on small islands, or near the coast on larger ones, and corrosion caused by sea spray can get pretty severe. Materials and techniques that were commonly used elsewhere in NOTA completely failed here. At station CN46 on Carriacou, for example, the connection point between the GNSS antenna and the monument rusted so badly that hurricane winds blew it clean off, never to be seen again. While the monument was made of stainless steel, the electrode used when arc welding it together caused an electrochemical reaction that left it vulnerable to corrosion.

So step one was ensuring that no bolt, bracket, or weld would be susceptible to corrosion.

Next was designing to withstand hurricane winds and storm surge. All these stations require solar power, and solar panels mounted several feet off the ground have experienced rapid unscheduled disassembly by winds on multiple occasions. As for storm surge, while large plastic cases successfully house electronics for many polar instruments, buoyancy hasn’t been a helpful property for inundated sites in the Caribbean.

The new design is built around a condensed, all-in-one concept. Starting from an available heavy stainless steel chest, Adam added mounts for solar panels (backed by solid plates) and an antenna for telemetry. Everything stays compact and close to the ground, greatly reducing wind exposure. (This does mean they need to sit in a spot with little vegetation.)

The ventilation openings are covered with a breathable but waterproof fabric to keep rainwater out. The chest itself adds about 100 pounds, and once four or six batteries are placed inside, the total weight is around 400 pounds. With such a dense package, they shouldn’t need additional anchoring into the ground to stay in place during a storm.

Into the storm

Station CN11 is located on one of the Pedro Cays — tiny islands south of Jamaica. Getting there from the mainland involves hitching an 8-hour ride on a Jamaican Coast Guard boat, and maintenance work has to be finished by whatever time that boat wants to leave. For the visit in April 2025, that meant Adam and our partners, Paul Williams and Paul Coleman of the University of the West Indies, Mona Earthquake Unit, had about four hours to replace equipment at the station and bring it back online.

Fortunately, the chests can largely be pre-configured. They dropped in the batteries, connected up the wiring, ran the GNSS antenna cable into the new enclosure, and CN11 was up and running again.

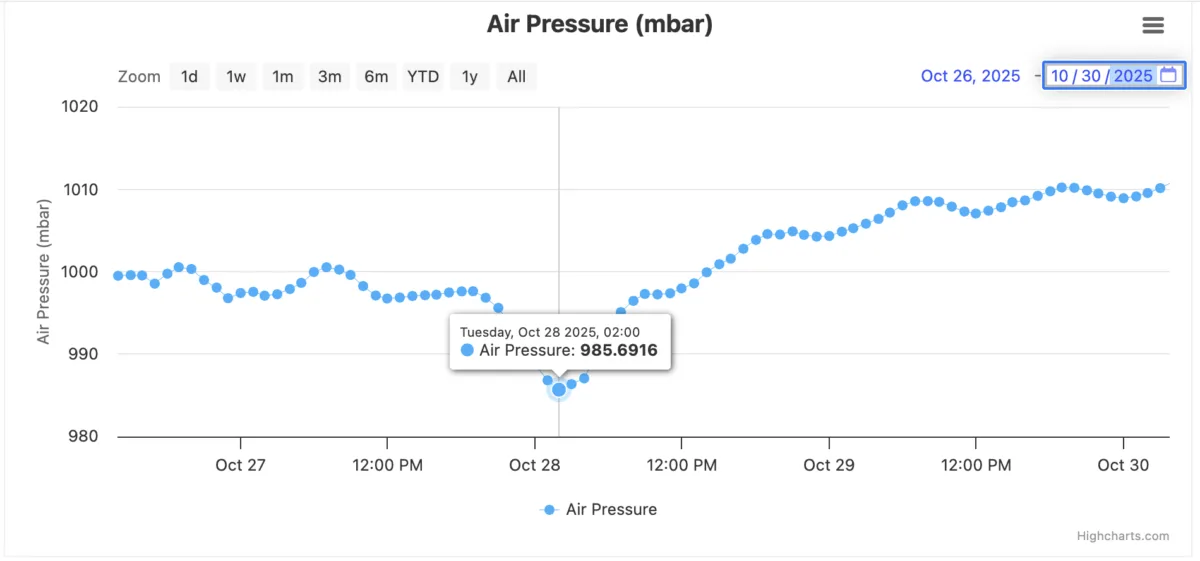

But on October 28th, Hurricane Melissa hit the area as a category 5 storm. Adam kept a close eye on the connection to CN11, anxiously waiting to see if all the work would pay off. Except for some intermittent delays as the Starlink connection struggled with the thick storm clouds (thick enough to prevent solar panel charging for two days), data from the GNSS receiver and meteorological instrument pack did continue to flow throughout. There was no sign of trouble with the power system or other equipment in the new enclosures.

But… the quality of the GNSS data suddenly changed. The signal-to-noise ratio degraded, and the number of GNSS satellites being tracked dropped. When someone was finally able to get eyes on the station in December, the reason became clear. The enclosures were unperturbed, but a large piece of building debris had smashed the GNSS antenna.

It may not be able to protect the rest of the instrument from flying wreckage (a visit to replace the antenna is in the works for March) but the chest design acquitted itself well in the extreme conditions. With further iteration, it’s being put to use at more sites — mostly recently one in coastal California — and should be a good solution for more stations in the Caribbean.

Adam Woolace and others on the Common Sensor Platform team have been working on improving and standardizing equipment for different types of deployments. Another unique environment recently getting the strong-steel-chest treatment, for example, is the deep snowpack common at high-altitude volcano-monitoring GNSS stations in the Cascades. In both cases, a little extra engineering can maximize uptime for important but hard-to-reach stations so that they’re online and recording for as much of the next “dynamic event” as possible.