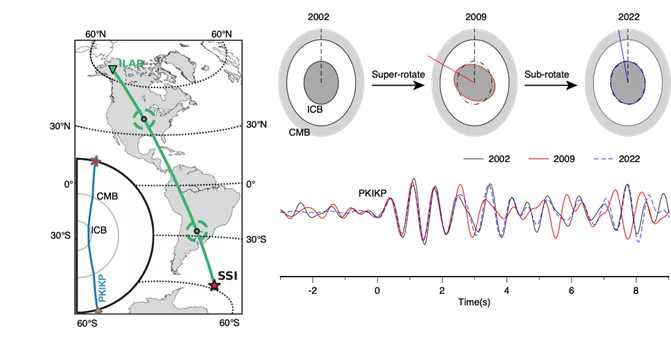

Earth’s inner core—the solid ball of iron and nickel surrounded by a melted, sloshing outer core—changes its rotation relative to Earth’s mantle every so often, and sometimes reverses altogether, a team of scientists reported in a 2023 Nature Geoscience paper. In particular, they found that prior to 2009, the inner core experienced super-rotation, in which the core rotated eastward relative to the mantle. Curiously, approaching 2009, this differential rotation between mantle and core slowed before changing to westward rotation after 2009, according to the paper. This finding came from studying more than 200 earthquake doublets, which are pairs of quakes that occur in the same location with about the same magnitude. Ostensibly, doublets should produce the same signals at a given seismic station. In reality, if something changed along the path the seismic waves took through Earth, that change would be recorded in the data.

One path in particular that’s taken by many doublets is special, says coauthor Xiaodong Song, a professor at Peking University. This is the SSI-COL path, “which has a long recording history and is the initial path used for the first detection of inner core rotation.” (SSI stands for earthquakes in the South Sandwich Islands, and COL for a station in College, Alaska.) With 31 doublets from this path, the team reported that beginning in 2009, inner core rotation seems to have started to slow as part of a seven-decade-long cycle.

However, in a March 2024 paper published in Geophysical Research Letters (GRL), Hrvoje Tkalčić a professor at the Australian National University, revisited the SSI-COL dataset and argued that the model used in the 2023 study strongly depended on the input data. When all available data are considered, the results, he says, are less clear. “The period of fluctuating differential rotation [is] shorter,” he says, with a 20-30 year cycle appearing rather than a 70 year cycle when several more doublets are added in.

And, in yet another recent article published in Nature, a team led by Wei Wang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences also focused on the earthquakes generated in the South Sandwich Islands. But instead of using data from COL, they focused on seismic data taken from two short-period, medium-aperture seismic arrays—the Eilson (ILAR) and Yellowknife (YKA) arrays (ILAR is located near COL). Because these arrays have twenty or so stations, the data can be combined to reduce the noise, which cannot be done with a single station. This team found that the inner core moved eastward relative to the mantle from 2003 to 2008, and then went westward two to three times more slowly from 2008 to 2023, essentially reversing itself. “The result confirms the 2023 model from Song for the last 20 years with more precise and unambiguous readings,” says coauthor John Vidale, a professor at the University of Southern California.

Even before these three studies, different papers proposed fast rotation, slow rotation, or even none at all. Studies concluding no rotation instead attributed the observed differences in certain doublets to changes in topography at the boundary between the inner and outer core. The questions at hand today are: If the travel time differences seen in doublets are related to differential rotation of the inner core compared to the mantle, what period does this rotation oscillate over? Does this rotation fluctuate fast or slow? And perhaps most fundamentally, does the inner core rotate at all?

Spinning, switching core

“The deep Earth is an integral part of the dynamic Earth system,” Song says. “The inner core motion is a rare chance to ’see’ the internal operation of the deep interior of the Earth.”

Earth’s core, split into two layers, contains a solid metal inner core wrapped in molten metal that forms the outer core. The metals in the liquid outer core, swirling turbulently at high temperatures, generate a self-sustaining magnetic field. This geodynamo manifests itself at the surface as the magnetic north and south poles, with the magnetosphere enclosing Earth, forming a bulwark that, incidentally, protects life from space rays. The strength and switches of the magnetic field—north becomes south and vice versa—directly relate to the degree and pattern of sloshing in the outer core. The more frenetic the motion, the stronger the magnetic field.

“Magnetosphere generation doesn’t care about inner core motion, but it may well cause the inner core motion,” says Vidale. “The outer core likely pushes the inner core around.”

Magnetic coupling and the distribution of mass in the mantle play key roles in this process, Vidale continues. “It’s all mostly iron down there with strong magnetic fields, and so when the outer core flows past the inner core, it tries to carry it with it,” he says, resulting in magnetic coupling. The mantle has also heterogeneously distributed material along the core-mantle boundary, and this density heterogeneity distorts the geoid of the inner core, elongating it by about 100 meters, he says. “The general idea is maybe it has a 70-year period of swinging back and forth, trying to line up with the mantle,” he explains, “and there’s a problem with that.” The problem is that theoretical calculations suggest the swing should amount to five to ten years, not 70. “I’m not convinced it’s an oscillation at all,” he says. “[The inner core] might just be wandering and deforming to retain the shape of the geoid.”

Using doublets

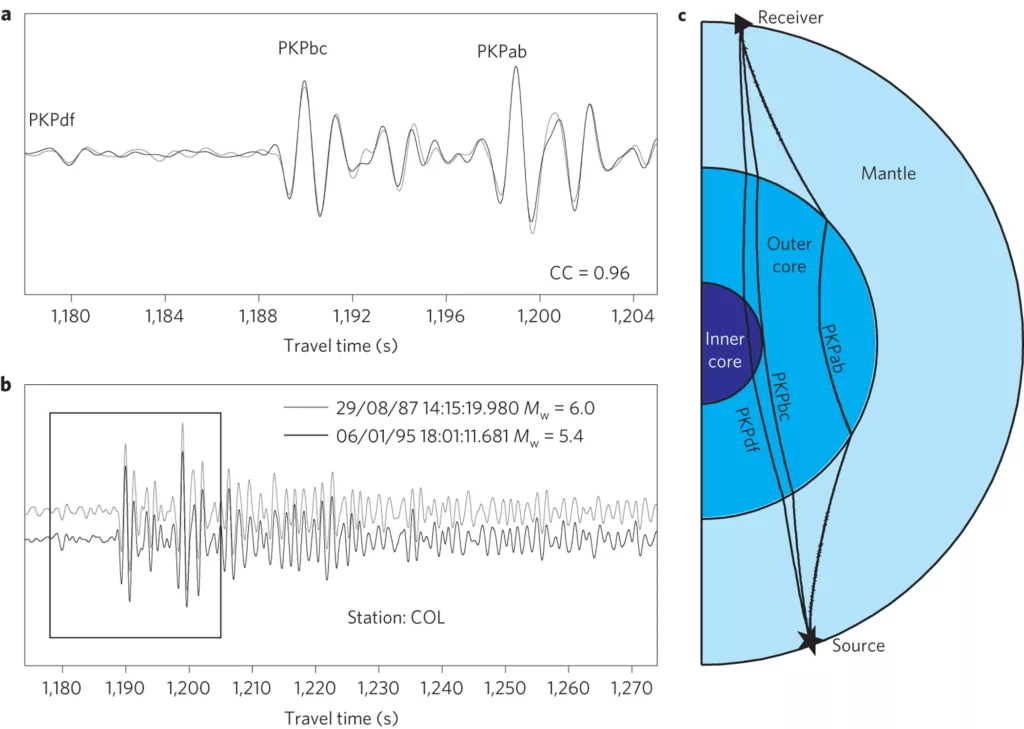

When earthquakes occur, body waves—P and S waves—take different paths through Earth. They can bounce off structures where material properties change; this is called reflection. Or, they can travel through these boundaries, but at a new angle because of the change in material properties; this is called refraction.

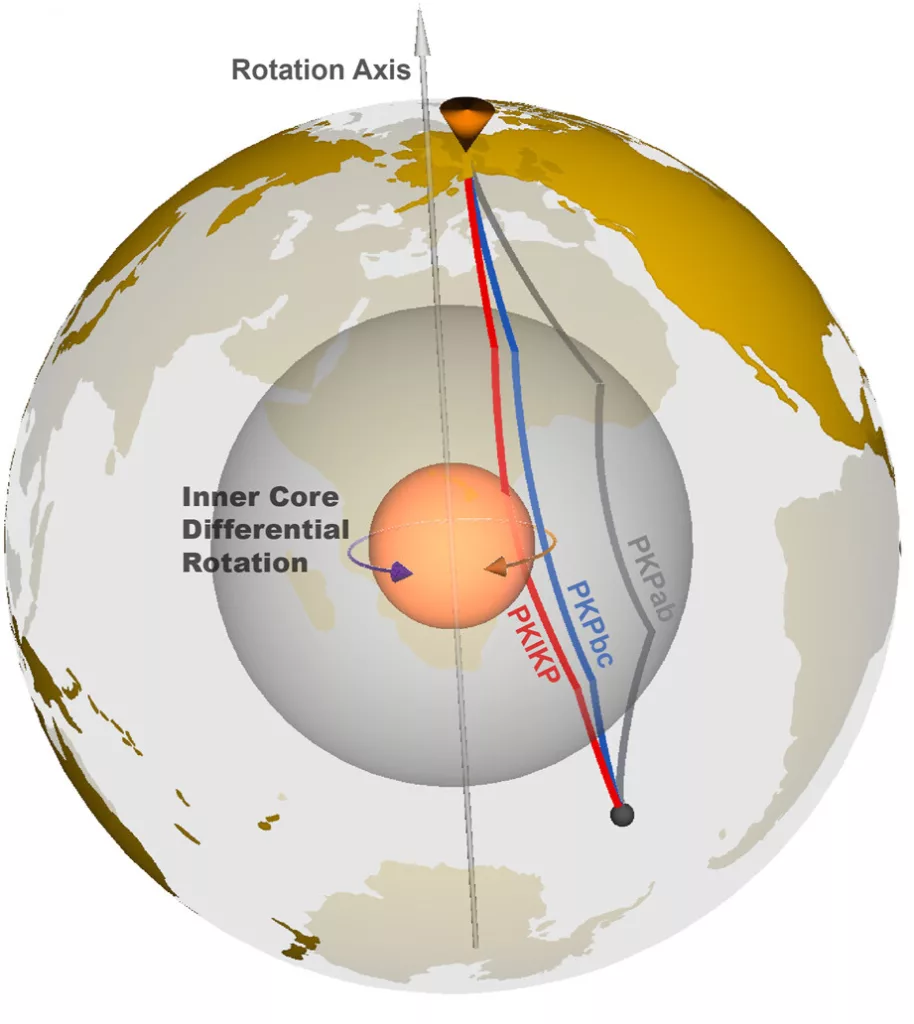

The PKIKP phase refracts its way to the inner core, sampling the enigmatic center of our planet. P-waves that traverse the inner core are labeled I, and P-waves that travel the outer core are labeled K. In the case of earthquakes in the South Sandwich Islands, the PKIKP phase travels as a P-wave from the south Atlantic Ocean, through the mantle, outer core, inner core, outer core, and mantle, back to the surface. These phases aren’t measured everywhere; most waves come to the surface in Alaska and northwestern Canada.

Doublets not only occur in the same location and with the same magnitude, but their focal mechanisms—the way Earth breaks—are also similar. Sometimes, more than two earthquakes occur, referred to as multiplets. When seismic waves from such earthquakes travel through the inner core to be measured at distant seismic stations from the earthquakes’ epicenter(s), seismologists look for changes in travel times to tell them something about changes deep within Earth’s interior.

“There’s a wave that goes through the inner core, there’s another wave that misses the inner core, and most studies are trying to say: Did the time between those two waves change?” explains Vidale. This is the procedure followed by both the 2023 Nature Geoscience and 2024 GRLpapers. The idea is that the wave that hits the inner core is going to change in proportion to how much the structures in the inner core changed. “If the inner core is just a radial structure, it can spin as a whole and it’s not going to change the waveform nor the time,” he says.

Doublet analysis and other methods have confirmed that the rotation of the inner core is not constant. The 2023 Nature Geoscience paper compared the changes over time along eight paths sampling different regions of the inner core. They found that the inner core slowed its speed relative to the mantle around 2009, says co-author Yi Yang, now an assistant professor at Nanjing University. In the 2024 Nature paper, that team looked at differences in the doublet waveforms and how they changed. “We’re basically saying when the waveforms match, the inner core has gone back to the same position it had at some previous time,” Vidale says.

Choices

In the 2023 Nature Geosciencestudy, the team excluded several doublets that, when used, yield different results. These doublets were discarded because, the authors note, the initial arrival of the seismic waves that sampled the inner core was weak compared to the preceding noise (you can think of this as a low signal-to-noise ratio).

Tkalčić argues in the 2024 GRL paper that these data should not be discarded for a variety of reasons. “The data selection based on their noise alone might lead to omitting data critical to achieving a well-conditioned problem,” he writes. In other words, not using data because of the low signal-to-noise ratio could remove valuable insights into the question at hand. By including these data, Tkalčić finds evidence for shorter rotation cycles, on the order of about 20 years.

Song notes that these short-term cycles found by Tkalčić’s analysis should be verified by with data that has high signal-to-noise ratios. “When the dataset is small—31 doublets—the inclusion of small numbers of noisy data could influence the fitting result,” he says.

In the 2024 Nature paper, Vidale and colleagues found that when matching waveforms from doublets and multiplets, the most important part of the signal was the end, also called the coda. “The waveform changes more and more as you go back into the coda.” And Vidale doesn’t go back further than about 20 years because “those arrays weren’t there before roughly 2000.” The periodicity that Tkalčić sees, says Vidale, requires looking before 2000. “We haven’t seen that kind of 20 year period of motion back to 2000. It’s possible, but it would be surprising if it were present only when there is not good resolution,” he says.

Future work

“There are limits on how much we can do,” Song says. He points to the tremendous efforts that have been made to dig up historical data. And certainly, waiting for more data is an option. “But we need to ensure continuous funding for station operations,” he emphasizes, and notes that archiving data properly is of utmost concern.

Vidale notes that a few scientists don’t buy the interpretation that the inner core rotates at all. In this alternate interpretation, “the surface of the inner core changes,” perhaps via the circulation of the outer core pushing the boundary up and down, he says. However, he points out that when the inner core appears to have backtracked with matching waveforms, “it gets to be too much of a coincidence” for the topography of the inner core to change to exactly what it was before, especially across multiple time intervals. “We see matches, and the matches all agree on where the inner core retraced its steps, but there are also pairs that slightly mismatch, that should have matched, so perhaps more than just rotation is happening.”

“There’s a pretty lively feud going on,” Vidale says.

“The current debates represent what science is: the search for truth,” Tkalčić says, noting that studying the inner core is challenging. “A tiny community of researchers in this field of study thus needs to continue to be highly innovative and, at times, keep challenging each other.”

More scientists diving into the problem would also help. The data from all three studies are openly available via the NSF SAGE archive. “Careful studies by more people would be a good thing,” Song says.