California has a new plan to work towards a sustainable future by harnessing its offshore winds, a key element in achieving its ambitious renewable energy goals. Passed in 2018, Senate Bill (SB) 100 is a law that aims to source 100 percent of their retail electricity—powering homes and businesses—from renewable sources by 2045. This policy has an ambitious target, but California’s unique resources can make this attainable. A recent study has proposed a unique way for distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) to play a role.

A recent advancement in SB 100 is a plan to deploy offshore wind turbines, capitalizing on higher and more consistent wind speeds. Harnessing this specific resource is key for attaining the goals of SB 100 while also considering possible environmental impacts and long-term safety. By the numbers, wind energy in California currently provides about 7% of electricity. These new offshore wind turbines are projected to be able to power about 25 million homes, putting a dent in the 148,000 MW of new electricity generation needed to meet the objectives of SB 100.

That additional power will be created through wind turbines atop stationary steel towers. Because wind is inexhaustible, this creates a clean renewable energy source. When wind speeds reach about 6 mph, the blades will begin to rotate. One rotation can power one home for a whole day. Even at those minimum 6 mph wind speeds, the blades rotate about 10 to 15 times per minute. California’s offshore wind conditions are perfect for this new strategic plan, as offshore conditions provide stronger, more reliable winds.

Installing these turbines presents its own unique challenges. The foundations of these are anchored to the seafloor and tethered to a floating turbine, so picking the proper spot requires a lot of consideration. An uneven or unstable seabed is a potential safety issue—if the foundation moves or cracks, the whole turbine becomes a hazard.

Additionally, California’s offshore waters are home to diverse marine life, and these turbines could disrupt their habits and migration patterns. Special consideration needs to be taken for the possibility of both geophysical events and marine life that could impact the integrity of the structures.

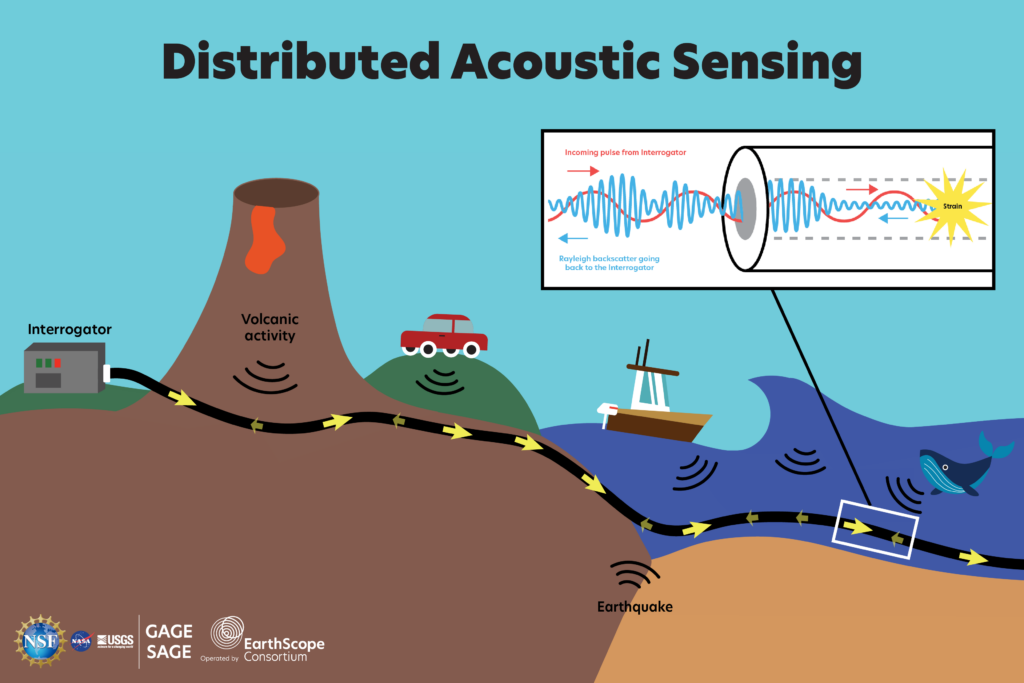

DAS has unique capabilities, capturing data across vast distances. Instead of relying on a few traditional sensors placed at fixed locations, long, fiber optic cables can be used—think of it like a ton of microphones attached to a string listening to the environment. This cable is connected to an interrogator—a device that continuously sends light pulses through the cable.

Any vibration or other deformation of the cable (like seismic activity, whale calls, or even temperature changes) disrupts the pattern of light reflecting back to the interrogator from tiny imperfections in the cable. By analyzing these patterns, researchers can determine the location of the source of the vibration and, from more details, can try to figure out exactly what it was. By simply running a fiber optic cable along the bottom of the seafloor or other target areas, researchers can gather continuous valuable data across longer distances with much less direct intervention.

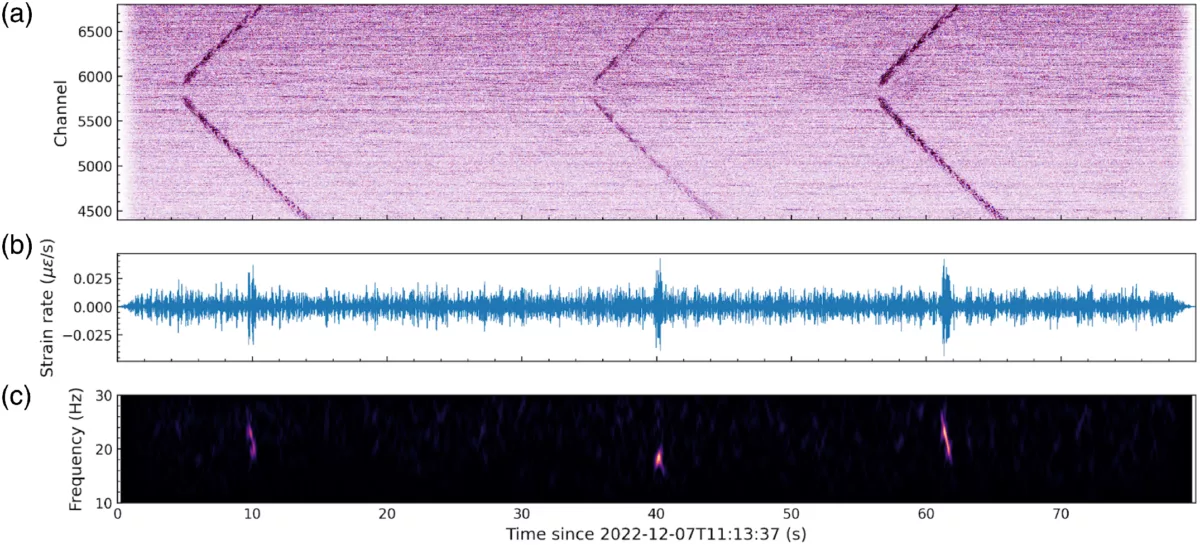

This new study proposes using many of the optical fibers already on the seabed in areas of potential offshore wind development and adapting them for these endeavors and new goals. They demonstrated the strength of this idea by looking at an existing cable in the Morro Bay area of California. By recording and analyzing earthquakes, they could create an image mapping the subsurface. From that they could identify fault locations―which were consistent with already mapped ones, along with four new unmapped ones. Identifying these types of seafloor hazards is essential for knowing where to anchor the wind turbine tethers.

The other concern is for marine life in the area. DAS is capable of helping with that as well, since it can also record acoustic waves. They tested this on areas with known whale species migrations and based on the frequency and duration of the sound, they could not only pinpoint the whale calls, but also infer the kind of whale making the call.

They can use these details to continue to locate and track the whales (or other marine life in the area) in order to see patterns and hotspots for migration. By monitoring marine life in this way, more informed decisions can be made about where to tether wind turbines in order to mitigate the disruption to marine life in the area.

Using DAS can provide California with an efficient way to get a more in-depth assessment of the seafloor and life where they plan to place these new wind turbines. In many cases, there are already optical fibers in place, they just need to be adapted for this use case. The proposed plan to deploy offshore wind turbines could make great headway towards California’s goals outlined in SB 100, and provide cleaner power for the area―and DAS could help provide information needed to limit any harmful effects and potential hazards down the line.